A couple of guys as I was walking were like hey babe.

I’ll wear jeans just because it’s safer.

Oi bitch, oi slag, get your tits out you slag.

I always walk with purpose.

The other guy waiting there goes oh cheer up love.

I want to talk back but you’re taking that risk.

Oi you come over here, sit on my face.

His trousers around his ankles

just jerking off.

He slapped me across the face.

He said can I cum on your tits.

He was pushing the gate trying to get through and screaming.

It’s easier to pretend I don’t hear anything.

The excerpt from my research above, each line taken directly from a different woman, shows something of the range and extent of such intrusion, and how it acts to limit women’s freedom.

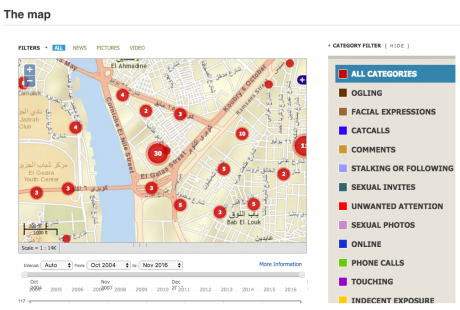

Attention to women’s experiences of intrusive men in public space is having something of a resurgence. Traditionally one of the most understudied yet commonly experienced forms of violence against women, the renewed focus is due in no small part to the ways in which digital platforms have been harnessed to make the experience visible, with apps like Harassmap used to show the scale of such practices, or the use of social media to share videos like this one from Imkaan and the End Violence Against Women Coalition, capturing Black women’s testimonies of how sexist practices are racialised.

Credit: Harassmap.org

Combined with this, direct action has been skilfully and creatively mobilised by women worldwide. From the encouragement for women to take up space seen in both the Why Loiter and Girls at Dhabas movements, to the art of Tatyana Falalizadeh and the energy of Hijas de Violencia (the Daughters of Violence), women and girls are pushing back on the ways in which men’s practices constrain our movements in public spaces.

This new wave of activism and awareness gives us an opportunity to reflect on our concepts, and strategise our responses. To rethink the commonplace framing of such practices under the heading of ‘street harassment’.

The term ‘street harassment’ is drawn from the pioneering work of Catharine MacKinnon and Liz Farley to define sexual harassment in the late 1970’s. This work originally aimed to mark out occupational sexual harassment in order to provide a structure for legislative redress, though it was later broadened to include educational institutions, an increasing area of policy focus today from sexual harassment in schools, to sexual harassment in universities.

But when our aim shifts from seeking legal redress to finding ways of articulating women’s experience both to the wider realm and to ourselves, we find aspects that can’t be captured by legalistic terminology. Aspects that may be better captured through the language of intrusion.

Intrude [verb] in·trude \in-ˈtrüd\

The deliberate act of putting oneself into a place or situation where one is uninvited.

The reliance of legal definitions on objective measures and binaries (either something is ‘street harassment’ or it is not) fails to capture the ways in which intrusive men choose and use ambiguous spaces. We are taught to doubt, dismiss, deny. Nothing really happened if it can’t be verified beyond what it feels like to us, and who do we think we are? Women’s experiences are never the source of authoritative knowledge about the world. The knowledge that informs the law.

A legal framework, such as that which underpins the concepts of sexual and street harassment, can assist in recognition of experiences as harmful. But it can alienate anyone who does not feel entitled to legal redress, or those who have witnessed police violence played out on their bodies and those that they love. The position of the law as an assumed objective arbitrator of acceptability means the epistemic norms and terminologies within it can be taken up as dominant narratives, silencing experiences that legally ‘do not count’. Setting the limits of what can be said. We lose the ability to talk about ambiguity. Those times where something both did and didn’t happen, the impact of anticipation – those times when we’ve thought maybe…

Maybe we’ll just sit over here, get on the bus, do a quick scan, and we choose

the seat closest to women, or closest to the driver, or catch the next train, just

to be safe. Or maybe we’ve pulled out our phone to avoid being stared at,

called someone to avoid being spoken to, stop when we get off the bus, not

sure if he’s following just wait back to see. Cheer up love it might never

happen. He might not be following you, touching you, staring at you. But it

feels like he is. Or he could. It feels like the last time he did, the last time the

last 'he' did.

Possibility itself can be intrusive, pushing its way into our awareness, uninvited. But none of this can be claimed as sexual harassment using any available definition. Where the legal frame struggles, our experience becomes unspeakable. So we don’t speak enough about how we changed routes home just in case something happened, and we stay mostly silent about the times when we actually didn’t feel harassed. When we are amused, complimented, bored.

We know the notion of a universal ‘women’s experience’, singular and shared, applicable to all, works to reduce us by denying women access to the multiple positions, contradicting and competing, that can be occupied by subjects. And legal frameworks struggle here, with how the same act can be defined differently both between different women and by the same woman in different contexts. The frame of harassment works to suggest that practices not experienced this way are unproblematic, leaving no space to explore the impacts of intrusions that may be experienced as wanted or desired. But we know there are consequences. The process of routine interruptions into women’s internal world, a disruption not only of one’s time to oneself but one’s time in oneself, has outcomes irrespective of whether such interruption is experienced as pleasurable.

That sudden feeling of being pulled outside of yourself, without wanting, without warning.

Interrupted.

Disrupted.

Intrusion allows for a broader range of practices to be addressed. It foregrounds the actions of the perpetrator, rather than our response, honouring women’s autonomy – our ability to make meaning in multiple ways. So too, ‘uninvited’ unlike the usual ‘unwanted’ affirms our power to choose who is able to enter into our physical and emotional space. As a verb it sits more closely to how such practices are lived, where one’s inner world is entered into, rather than solely acted on.

Such a shift may have limitations. We could lose some of what we gain in locating practices as harassment: the power for legal redress and acknowledgement of harm. Or struggle in mobilising social change, losing the gains of ‘street harassment’ as a widely understood concept. But we must remember in expanding our terms, one frame need not replace the other. And the existence of limits doesn’t ever mean we shouldn’t push against them.

Men’s intrusion: one response to the challenge of finding language that springs from our internal knowledge rather than conforming to the needs of a structure.

There are so many more.

Let’s find them.

Read more articles on openDemocracy in this year's 16 Days: Activism Against Gender-Based Violence. Commissioning Editor: Liz Kelly

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.