New Delhi: On a warm day in June 2015, close to a hundred girls of Indraprastha College, Delhi University entered their university-provided accommodation in north Delhi, to find that bathrooms in their hostels did not have latches.

Uncertain and fearful of demanding this basic right, some of the girls sent an anonymous letter to the warden requesting latches to be fit in their bathrooms. The following day the principal directed all the girls to assemble in the lawns of the college. According to a student who was present there, the principal is said to have asked the students to honour the privilege of being accommodated in the hostel while thousands still seek it. The principal also reportedly asked the students to not send letters to her, and that she will do the needful when she deems fit.

Weeks later some of the latches appeared in the bathrooms.

“This points to how oppressed the girls in university hostels feel,” says Subhashini Shriya, M A student in Delhi University. “They can’t speak up for their basic rights, while you hear stories of boys beating up their wardens because their bread was not baked well enough!”

While Indraprastha College might be a stray case, most girls hostels in Delhi University do not have latches in the rooms. “So that the wardens can barge in anytime they wish to,” says Devangana Kalita, a gender studies student at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. The difference is that in boys’ hostels, absence of latches, if any, is not deliberate.

Both Shriya and Kalita have been actively involved in Pinjra Tod (Break The Prison), a collective of more than 50 girls studying in various universities in India.

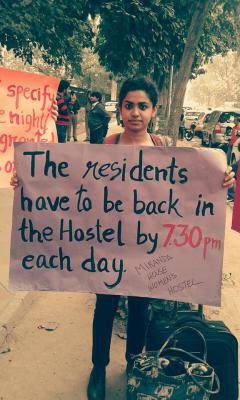

The Collective started, in August 2015, by protesting curfews in women’s hostels on college campuses in Delhi University. One of the first things the Collective did was to petition the Delhi Commission for Women to investigate women’s freedom in hostels, take action against moral policing and most importantly set up functional sexual harassment redressal bodies in colleges. Today, in less than six months, more than six universities are connected online under Pinjra Tod and fight gender issues together.

Such calls for gender equality, small and big, are not new in the 94-year-old Delhi University. In 2002, a group of girls from Miranda College had protested curfew timings in girls hostels pointing out that girls are forced to be back in their hostels before 8 PM, while the university library was open till midnight. In 2007, another group had protested the fact that girls’ hostels were locked up from the outside at night, making them prison-like. None of these norms hold for men’s hostels.

The problem seems to lie in the very perception of a hostel. In most cases, hostels are seen as extensions of homes. “This is your home away from home” were my warden’s first words back in 2004, in Lady Shri Ram College’s hostel. “Do not expect your duties and responsibilities to be any different,” she had added for good measure.

This approach ensures that the patriarchal structures at home are reflected in these lodges. The anxiety that is expressed at home when a woman doesn't return by dusk is the same in a hostel. A girl who ventures out post curfew time needs to get signatures from the warden and guardians, and report her destination to them in advance.

For most women, this exemplifies the contradiction between what they learn in colleges and what they see in practice. “When we are taught about women’s autonomy and freedoms, why aren't we told it is not seen in practice and is restricted to books?” asks Kalita. Rules of entry and exit are institutionalised in hostels, with heavy penalties for breaking them.

Shambhavi Vikram( centre). Photo: Pinjra Tod (Break the Prison Collective).

Shambhavi Vikram, a member of the Collective and a student of English Literature, believes that restricting freedoms is not a way to ensure safety. “They should work towards making our societies safe, not restricting our freedoms,” she says. “Those who believe that restricting freedoms would ensure safety are also those who believe that women are responsible for rape as they were skimpily clad,” she says.

Due to the curfew timings, says Kalita, there aren’t many girls who get elected to student unions, since elected members of the union are required to work several hours post dusk. St Stephen’s College, that prides on having produced one-third of India’s parliamentarians at one point, has had only two girls as student union presidents in three decades.

But, there is flip side, say the administrators of hostels. If there are no restrictions on girls’ movement post dusk, parents think twice before sending their children to universities. “We have many parents telling us that they want us to be as strict with their girls as they themselves are,” says a warden requesting anonymity as she is not authorised to speak to the media. They would rather not send their girls to the university than have them roam the streets at night, she says. “They do not say the same about boys,” she says.

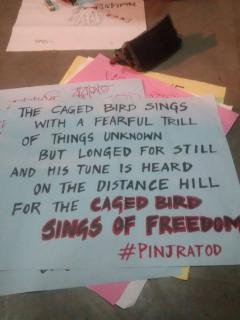

The name of the Collective, Break The Prison, is not merely indicative, says 24-year-old Vikram. The hostels actually are like prisons for many girls.

“Ironically enough, the language and terminology of hostels belie, or perhaps unconsciously underscore this, and are homologous with prisons! Typically, ‘wardens’ manage women’s hostels; students and women living in it are frequently referred to as ‘inmates’; the rules and conditions, especially regarding timings, visitors and ‘nights out’ are restrictive and unreasonable. All of these remind one only of jails.” says G Arunima, Associate Professor, Centre for Women’s Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University.

A drive around Delhi University at night looks something like this: largely deserted roads with the exception of men mobbing food carts that sell sought-after midnight snacks. Some boys walking back from the libraries at midnight, hugging the books. A bunch of boys huddled around a bench, talking politics. I even heard a loud recitation of Romeo and Juliet by a seemingly drunk male student on the pavement close to the highway.

“See that?” asks Kalita. “That is the problem. At night, public spaces are not for women. Unless we reclaim these spaces, we will never be truly safe,” she says. In December, a dozen girls from the Collective, started loitering the streets at night. They boarded buses and began singing songs, in an attempt to raise awareness about women’s freedoms. They plan to do so again in the near future.

Break the Prison Collective, New Delhi.Photo: Pinjra Tod

As their movement gains momentum, the Collective is taking up several other issues - forced marriages, menstruation and equality in education. They are also involved in protesting against casteism on campus after a student recently committed suicide in the southern city of Hyderabad unable to bear caste discrimination.

Higher education in India used be the bastion of the upper castes and economically privileged sections. Through the years, large-scale presence of state universities, reservation of seats and rising income levels have ensured the entry of lower castes and classes into universities in greater numbers. This can only mean that status quo will never be accepted unquestioningly. “Students should learn to fight injustice early,” our then principal, Dr Meenakshi Gopinath, had once mentioned, encouraging our active involvement in gender issues.

As a student of Delhi University in mid-2000s, the idea of the ‘personal being the political’ was engrained in me. We dove into protests that opposed violence against tribal populations, we campaigned for LGBT rights and petitioned for greater transparency in government functioning. However, the present fight seems to be more daunting in the face of a callous crackdowns by the police.

Vikram, Kalita and Shriya have all been detained and taken to a police station more than once when they attempted to demonstrate in larger numbers. “They just keep us there till around 7 PM and let us go,” says Kalita. According to older faculty members of the university, such barbarism is unprecedented.

While the girls of the Collective are happy with the support they got from the media, they can surely do with more of it.

In one of their reflective moments, Kalita says, “I think we got great media coverage because most of the journalists who covered us were women.” One of the only two male journalists who interviewed them, asked them if they weren't asking for too much by stressing on gender equality.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.