CALAMA, Chile—About 765 miles north of Santiago in the Atacama Desert, the Gabriela Mistral recreational center emerges as an unexpected touch of modernity among the sandy-colored mountains. Down a path of crushed stone leading to the cafeteria, the site is peppered with circle-shaped patterns made up of bluish-green rocks—a telltale sign of the presence of copper oxide.

Since opening in 2009, the striking installations at the Gabriela Mistral mine—or Minera Gaby—have been a source of praise for their innovative approach to mining and community development. More recently, Gaby has drawn the attention of scholars and government officials as an unconventional yet practical example of how climate-change-related measures are not only necessary, but also can be economically convenient.

In 2013, CODELCO inaugurated what was then the world’s largest thermosolar plant, Pampa Elvira Solar, to provide Minera Gaby renewable energy for its operations. With 2,620 glass and aluminum collectors arranged in the shape of CODELCO’s corporate logo—a large Venus symbol, the alchemical symbol for copper—the plant delivers 85 percent of the power needed for the hydrometallurgical process used to produce copper.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As a result, the mine not only cut back its diesel costs, but it started producing “greener,” premium-quality copper cathodes that are competitive in more aggressive carbon emission reduction-prone markets, such as Europe.

“We are at a crucial point in the division,” explained Alan Brell Salgado, representative of CODELCO’s Gabriela Mistral division. “Our carbon footprint is a very important topic for us, as we are taking the steps to obtain our certification and negotiating with the European market, which is stricter than the Chinese.”

In the wake of declining demand from China, the world’s largest copper market, the opportunities of a new market opening up send a strong signal to the mining sector. The industry has now found an unusual ally in nonconventional renewables. In Chile’s case, the economic benefits of going green have also been heightened by a recent push from the presidency to meet the country’s greenhouse gas emissions targets.

“This administration, [Michelle] Bachelet’s administration, is really prioritizing climate change in a way that no other previous administration has done, including her first administration,” said Amanda Maxwell, Latin America project director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit international environmental advocacy group based in New York City.

But the shift to a cleaner, more sustainable energy sector is easier said than done here.

“A lot of people would agree that Chile doesn’t have an energy generation problem, they have an energy transmission problem going forward,” Maxwell said, referring to an aging and inefficient electric grid. “I think people are starting to think about the depth of the changes that will be needed in order to allow renewables to really participate on an even playing field.”

Advocates say it’s slowly beginning to pay off.

Developing a ‘third way’ of climate politics

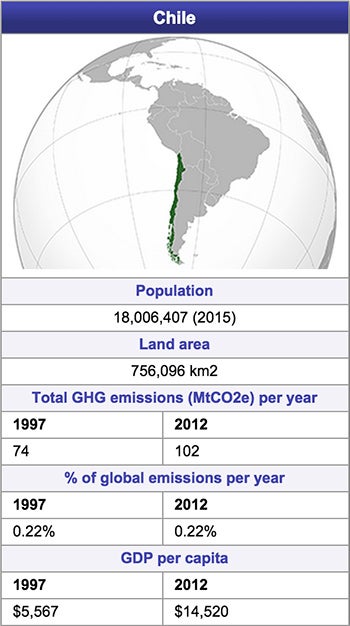

Chile may not be the kind of country that comes to mind when discussing the future of climate change. Its annual emissions are 40 times smaller than China’s and 30 times smaller than the output of India. Its economy, while long the strongest in Latin America, does not make the country a global powerhouse of political influence.

Still, Chile is beginning to play a pivotal role on the global stage.

Chile’s share of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions amounts only to 0.28 percent. But per-capita emissions have been on the rise over the last two decades. According to the country’s latest emissions report, emissions have increased by 83.5 percent since 1990. That makes it the second-largest per-capita climate polluter in Latin America, behind Venezuela, with an average of 5.3 tons per person. As the country continues to develop, these numbers are expected to grow.

After a contentious 2009 climate summit in Copenhagen, Denmark—which ended without a binding treaty after bitter battles between nations—Chile put its eggs in a new basket. It participated in the formation of a group called the Cartagena Dialogue, an informal space for countries committed to a low-carbon economy to work on a legally binding regime in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. It also became a member of the National Alliance of Latin America and Caribbean Communities (NAILACC), which promotes the need for nations to take part in climate mitigation actions.

“What I think is really great about Chile, and its partners in [NAILACC], as well, is that they are saying, ‘Climate change is a problem, but we need to develop. We are willing to make a transformation to low-carbon economies, but we need support,’” said Guy Edwards, research fellow at the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society and co-director of the Climate and Development Lab at Brown University.

“And I think this line of discussion, especially in the U.N. climate talks, is seen as a third way,” he said.

At the U.N. climate summit in New York in September 2014, Bachelet reiterated the country’s commitment to reducing carbon emissions and set an international precedent by announcing public consultations for Chile’s contributions to a new climate agreement that is expected to be signed in Paris at the end of this year.

The final target submitted to the United Nations at the end of September ultimately was less ambitious than some of the draft options that the Chilean government had circulated. The goal aims for a 30 percent cut in carbon intensity by 2030 based on 2007 levels. That target is unconditional, but Chile said it could go even further with financial assistance. At the same time, it pledged to reforest 100,000 hectares of forest.

In a blog post, the NRDC called the unilateral goal a “safe, conservative bet which Chile can meet and certainly exceed,” and called on Chile to meet the more ambitious end of its target. Still, the group and others said the energy conversation happening in Chile, particularly its call for public consultations, is a big step.

“I think Chile’s efforts are blurring the lines between domestic and foreign policy, and how climate change is an issue for both arenas to tackle simultaneously,” said Edwards. “As we gear up for Paris, the [NAILACC] countries are going to be potentially key partners to be pushing for a higher-ambition agreement.”

Institutionalizing climate action at home

Chile’s climate diplomacy spurs changes at home.

In 2008, Chile launched its first National Climate Change Action Plan, for the period from 2008 to 2014, to gather information on what was happening in the country, identify the baselines for emissions cuts and measure other key variables. But the biggest change came in 2010, when the Ministry of Environment was finally created, according to Paola Vasconi, a climate change specialist and coordinator of political affairs at Adapt-Chile.

“Chile was one of the last Latin American countries to create a ministry of environment,” Vasconi explained. “In a way, the creation of the ministry helped institutionalize climate change at a national level.”

Since then, the ministry has launched several projects, in collaboration with other ministries, to define and promote the government’s climate agenda. In 2011, it launched its Mitigation Action Plans and Scenarios program, or MAPS Chile, to determine the baseline for the country’s greenhouse gas emissions under business-as-usual conditions from 2007 to 2030. Those projections on how the Chilean economy would evolve without any efforts to reduce its greenhouse gases are expected to help define different mitigation measures and possible scenarios.

Officials have also been working on an update to the National Climate Change Action Plan, for the period from 2016 to 2021, oriented to the implementation and funding of mitigation and adaptation actions contemplated in Chile’s intended nationally determined contributions. The ministry also recently launched a project to determine how much the government has been indirectly spending on climate-change-related measures, as well as one to standardize the way companies calculate their carbon footprint.

Most importantly, because of the presidency’s explicit support, other ministries have also been taking on a more active role on climate change, Vasconi said. Progress began with the energy sector.

Unlocking green investments in a free-market economy

With the creation of the Ministry of Energy, also in 2010, the government launched an aggressive campaign to restructure the energy sector and define its agenda. The ministry recently submitted to the Chilean Congress legislation aimed at tackling energy efficiency.

Perhaps the most significant change occurred in 2014 with the modification of the bidding process for power generation projects. The reform split the hours of generation between day and night shifts, finally unlocking investments in solar. The country also introduced a carbon tax on generation and vehicle emissions, its top two emitting sectors.

“What Chile did was create an environment that enables green investments,” said Marcelo Mena-Carrasco, undersecretary of environment.

Credit: ClimateWire

Specifically, the tax on power generation includes a fixed cost of $5 per ton of carbon dioxide, plus a variable tax based on the pollution and environmental damage to the community where the plant is located.

“The second tax to power generation has a strong market signal effect, because you are adding the cost of negative externalities to the electricity generation,” he explained. This, according to Mena-Carrasco, levels the field between renewables and conventional generation in terms of operational costs.

From his office at the Ministry of Environment’s building, near the Palacio de La Moneda—the seat of the president—in Santiago, Mena-Carrasco has become a key advocate within the government for cross-ministry climate action. He has had to learn to navigate the murky waters of bureaucracy to sell the ministry’s mitigation and adaptation initiatives.

“In a free-market economy, it makes sense to a lot of people when you say that not having a green tax is a hidden subsidy, and that’s something that at least resonates among the more conservative economists,” Mena-Carrasco said.

As the agency works on its new energy policy, Energía 2050, there is growing evidence that climate actions can mesh with the country’s development goals. Targets like a 30 percent reduction in energy costs by the end of the current administration, 20 percent in savings on energy consumption through energy efficiency and a goal to achieve 20 percent generation from nonconventional renewables by 2025 are already being implemented to make Chile more competitive, Mena-Carrasco explained. They are also vital to Chile’s climate policy.

Will Chile’s grid stand in the way of its own progress?

After a timid start, the approval of the “Law 20/25” in 2013—which set a target of 20 percent nonconventional renewable energy (NCRE) generation by 2025—triggered a boom in NCRE, according to data from the Chilean Association of Renewable Energy (ACERA).

In 2014, NCRE practically doubled its installed capacity in December 2013, reaching 2,097 megawatts by December 2014. By May 2015, installed capacity reached 2,270 MW, with an additional 2,000 MW reported in construction. Experts say these statistics point to an estimated investment of $4 billion a year in NCRE, between 2014 and 2015 alone.

“Recent studies show that Chile has an estimated potential of more than 1.8 million MW in NCRE projects, including solar technology PV [photovoltaics], CSP [concentrated solar power], wind, mini-hydro, biogas/biomass, geothermal and marine,” said Carlos Finat, executive director at ACERA.

“This potential supports that in a reasonable time, by 2050, for example, the country could have an energy matrix based 100 percent on renewable energy, both conventional and unconventional,” he said. But that reinforces the need to update Chile’s electrical grid.

After the grid’s privatization in the 1980s, new transmission lines were built catering to specific projects -- particularly energy-hungry mines in the north. Meanwhile, cities were electrified almost as an afterthought. This led to an inflexible energy matrix, with serious shortcomings in transmission and little consideration for renewables. These are expensive issues.

In April, the government approved an expansion plan that calls for the construction of a transmission line that would connect Chile’s Central Interconnected System grid and northern Interconnected System of Norte Grande grid, and bring the clean energy in the north to the rest of the country. According to the National Energy Commission, the interconnection project has an estimated cost of $1 billion. And this is just one of the projects under construction.

A glassy economic oasis in the desert

Despite the cost, the value of solar power remains a bargain. Chile produces about a third of the world’s copper, and mining is by far the sector with the biggest demand of energy, representing almost 30 percent of total energy consumption. That number is expected to double by 2025, according to recent reports.

“The mining process itself uses a lot of electricity, but it also uses a lot of heat,” explained Cesar Belaunde, project manager at Energía Llaima, the company that owns and operates the Pampa Elvira thermosolar plant for Minera Gaby.

Covering almost 970,000 square feet of dry, rough terrain, Pampa Elvira stands out as a glassy oasis at the driest place on Earth. With the highest solar radiation in the world concentrated in the Atacama Desert, its collectors feed the mine more than enough heat necessary for the copper extraction process known as electrowinning.

An acid solution rich in copper called an electrolyte is heated to 47 degrees Celsius and pumped to a tank with insoluble lead plates and stainless-steel sheets. A direct current is then applied between the lead plates and stainless steel, causing the copper ions in the electrolyte solution to attach themselves onto the sheets. Thus obtaining the copper cathodes.

“Electrolytic copper is one of the purest coppers that can be obtained with the processes we have in Chile,” said Belaunde. And now, with thermosolar, it’s also a bit greener.

The benefits of using thermosolar power in mining processes are many. In the case of Minera Gaby, for example, the 39,300-square-meter solar plant can substitute about 80 percent of the fossil fuel used to heat the electrolyte solution with thermosolar power, saving up to 6,500 tons of diesel a year. By burning less diesel, Minera Gaby has also cut back its CO2 emissions by nearly 15,000 tons a year.

More importantly, “you get premium copper,” Belaunde added.

Can greening the copper mines green the country?

China’s economic deceleration, and the consistent drop in international copper prices, has led private mining companies in Chile to reduce their investments in new projects. As the Financial Times pointed out in April, this has left CODELCO with the burden of keeping up Chile’s share of the world market.

Earlier this year, the corporation raised $4 billion to finance new structural projects, spanning through 2025. According to Brell Salgado, now is as good a time as any to innovate and look for alternatives that would make the business much more sustainable and more resilient to the fluctuations in China’s demand for copper.

“The vision at the division today is that we are looking at a completely different scenario than we had yesterday. Today, we are betting to play in another league with copper of better quality, more efficient and more cost effective that will allow us to be more competitive and environmentally friendly,” Brell Salgado said. But this change in attitude didn’t happen overnight.

“It took us 11 years to convince CODELCO of doing it,” said Roberto Roman, solar energy expert and associate professor at the University of Chile. “But it’s finally catching on.”

According to Belaunde, Energía Llaima recently closed a deal with Minera Zaldívar—an open-pit copper mine in the Antofagasta region owned and operated by Barrick Gold Corp.—to install and operate a large thermosolar plant. There are currently only three thermosolar plants in Chile operating in copper mines; the fourth one will be in Zaldívar.

“I think there is an opportunity to take leadership in the particular topic of solar energy and mining,” said Roman. The model being implemented at Minera Gaby is evidence that climate change initiatives, such as pushing for cleaner energy, can have multiple economic benefits beyond reducing emissions. Market-wise, it’s smart business.

Chile has a long road ahead to solidify its climate change policy beyond the walls of the Ministry of Environment. As many civil society groups and officials point out, without a proper climate change law, it will be hard to steer powerful ministries like Finance and Economy away from their “business as usual”-oriented ways to a low-carbon future. But the fact that a conservative sector such as mining, famously resistant to change, has found a way to make the green business work for it shows a promising start.

“I think there is a huge opportunity in this regard, and many people are beginning to see it that way,” Roman said. “They realize that it is not a business issue of one mine, two mines, but a change in how you are going to do things, and that opens up opportunities that would be a shame for the country to lose out on.”

Reprinted from Climatewire with permission from Environment & Energy Publishing, LLC. www.eenews.net, 202-628-6500