This article was first published in July 2015.

In the weeks before Obama was pictured grinning with a Cuban cigar in hand, Havana was abuzz with talk of transformation. Besides the indelible lyrics of Enrique Iglesias and Descemer Bueno’s “Bailando”, the most common refrain heard on the streets of Havana is that life is changing. A small island with a large sense of history, the Cuban people are used to shifting currents. But how life is changing and for whom seems less certain.

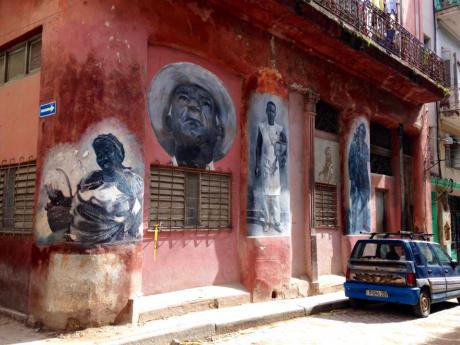

Street art, Havana (photo: Jennifer Allsopp)

I spoke to women in Havana in the weeks before December 17th. I was in Cuba with a cultural exchange group, my fifth trip to the island. I wanted to hear from Cuban women how they conceptualise change and progress in their lives and in the life of their nation.

I meet up with Yusumi, a 40-year old filmmaker, at the ice cream parlour Coppelia. We chat about her life, her goals and her view of feminism in Cuba. Last time I saw her was 4 years ago in the eastern city of Holguín. She is sporting a new hairstyle and new sense of confidence.

When in 2011 President Raúl Castro changed the laws controlling private enterprise, Yusumi leapt at the opportunity to move to Havana. She has returned to film school to finish the degree she left 19 years ago, age 21. She care-takes a small apartment for friends and supports herself by doing freelance translating and guiding work. She is living a life that was unthinkable three years ago.

Yusumi turned 18 at the beginning of the Special Period. She felt her life was put on hold and watched as many of her contemporaries and older artist role models left the country. “It was a time of mass exodus. Those of us who stayed felt as if we had no one to look up to, no model to follow. We were hanging from the paintbrush - the ladder was pulled out from under us.”

Street art, Havana (Photo: Jennifer Allsopp)

She withdrew from art school, married and put her artistic ambitions on hold. Last year she separated from her husband of 15 years. He was not ready to embrace the opportunities that she was excited to pursue. She felt they were growing apart, she looking forward, he content to do just enough to get by.

“Things are changing; there are many more opportunities now. Cubans have gotten so used to living with restrictions that sometimes they do not see these new chances that are in front of them.”

“I am inspired by the younger generation,” she continues. “They do not want to leave Cuba. The future they are dreaming about is here. ‘Why would I want to go,’ they say, ‘when I can be happy and make a living here in my own culture?’ ”

Young musicians at the 'Cuban Art Factory' (Photo: Jennifer Allsopp)

“Do these economic reforms have a particular impact on women?” I ask.

“What you have to understand,” replies Yusumi, “is that feminism looks different in Cuba. From the beginning of the revolution, certain rights, to equal pay and education, to health care and maternity support, were institutionalised. The platform created by The Federation of Cuban Women has given women social mobility and this has liberated us from the need for extreme feminism, which to me is the woman trying to take on the role of a man.”

“With the changes to the economy, a woman can stay at home and perform a ‘feminine role,’ making artisan crafts, cooking, running a private guesthouse, and make much more money than her husband who is an engineer. This gives women a new sense of confidence.”

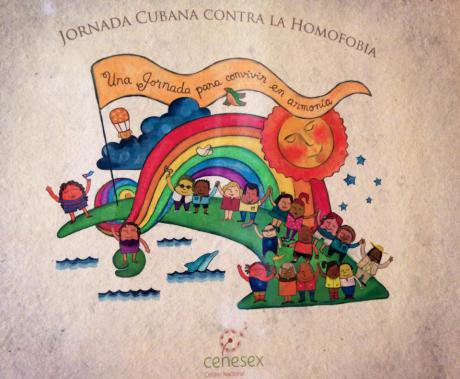

“Another thing that is changing,” she adds thoughtfully, “is the recognition and acceptance of homosexuals.” It is not lost on either of us that Coppelia, the backdrop to our conversation, was the scene of 1990’s film Fresas y Chocolate, a film which exposed the repressive treatment of homosexuals and did much to galvanise the gay rights movement in Cuba.

Poster: Cuban Day Against Homophobia (Photo: Jennifer Allsopp)

Yusumi sees the barriers to gender equality more in terms of culture than economics. “We still live in a patriarchy, upheld by cultural ideas of ‘machismo,’ ideas that limit possibilities for both men and women.”

I catch up with Anna on the top floor of the Hotel Riviera, built in the 1950s by American mob financier Meyer Lansky, a looming brute of a building, meant to intimate as much as attract, a reminder of the last era of American involvement in Cuba. We stand looking out upon the city, the neighbourhoods of Vedado and Centro Havana to our right, the Malecón and the open sea to our left, Havana Vieja away in the distance.

Anna is 28 and already a visual artist of repute. She has been sponsored to travel and exhibit several times in the US and Europe. Her art has given her the opportunity to see the world beyond Cuba, as few Cubans have been able to do.

“What I see in Cuba is a growing inequality between people. Those who have access to money and opportunities and those that do not. And this new class of wealthy people, they have no taste, they have made their money in small time scams and now are buying up property.”

“I am afraid,” she tells me, “of my country becoming like other places I have visited. I went to Columbia last year and there is such a large difference between rich and poor. Up until now Cuba has not had that problem.”

55th Year of Revolution (Photo: Jennifer Allsopp)

We move on to chat about the apartment she bought in Nuevo Vedado. With the money she saved she was able to buy the run-down apartment at a pittance and renovate it. She is now thinking about selling it and buying another derelict property in Havana Vieja, the old city centre.

The emergence of a property market is a very new phenomenon in Cuba, birthed in 2011 by legislation introduced by Raúl Castro. For the first time since 1959, Cubans are able to buy and sell their own homes. Until now houses have passed through families or exchanged hands via trade or the black market. Homelessness is practically nonexistent, although overcrowding can be an issue. There is very little economic segregation in housing. A colonial mansion in the city centre is as likely to be inhabited by a pensioner as a doctor, government official or Miami returnee.

Anna worries that in five years time the social mix of Havana will have changed, that Cubans will no longer be able to live in Havana Vieja, priced out by Europeans and Cuban expats returning from Miami.

When I ask her about the future of the country, she says, “Cuba will not be as we see it now. There will be a rise in materialism. Cuban people do not consume because they do not have the opportunity. Given the opportunity, they will consume more than anyone because of this scarcity mentality.”

I meet up with Tanya, a theatre actress born and raised in Havana, in a small park in Havana’s Vedado district. In a country where theatre is affordable and culturally accessible for everyone, her face is well known. Her career in theatre began when she was 15 and saw a production by the Havana based company Palpito. Enthralled, she committed herself to theatre. Twenty years later she is still passionate about her work. She attended the Escuela Superior de Artes, a premier art academy which offers free training to some of Cuba’s most influential artists. She remembers her university experience during the mid-nineties when Cubans were living through the Special Period. “Many people feel traumatised by this time. Myself, I wish we had not lived it, but I do not look back with a sense of tragedy. It was something we had to survive. I remember walking for blocks during the many blackouts to read books for my theatre courses under the one working street light. But I did not think of leaving. I was passionate about what I was doing.”

Street art, Havana (Photo: Jennifer Allsopp)

I have just been to see her current play, a two woman show which she co-wrote with two of her close friends from acting school. The play, called “Escape,” is based on the film Thelma and Louise and is not set in Cuba. “I am not interested in political plays,” she says, “I want my plays to inspire people to change, not point a finger at them and force them. Cubans have enough material difficulty in their lives. For me theatre should be enjoyable - not superficial - but a diversion from the everyday.”

I ask her about the economic reforms in Cuba. “The changes that the government have made [in allowing more private enterprise] are superficial, and people, now that they see a little bit of change are jumping on the opportunity to claim more for themselves. The government could take away the ability to have a license tomorrow. And there would be no recourse. People are not in the habit of asking why.”

I heard this concern voiced elsewhere, that capitalist growth will not necessarily lead to more happiness or social harmony. I wonder what she imagines happening in Cuba’s future.

“Some people would like Cuba to look like Miami. That idea terrifies me... Honestly I don’t know what is going to happen. I don’t want to leave Cuba. I am a Cuban who loves Cuba. Some of my best friends have left the country and now live abroad. If I can change anything I would like to do it from here, from where I am in my work, in my own city. The question is how. There is a belief among Cuban people that there can only be one leader. I want the kind of change that comes from the bottom, from the grassroots, profound change. I want to see individual people believe that they can be leaders.

I am interested in changes that bring more liberty, not the liberty to throw a rock through your window, of course, but the liberty to throw a rock up in the air and catch it, if that’s what I feel like doing.”

When I ask Tanya how she sees her own future, she tells me she would like life to get more and more simple. More than anything she would love to have a little piece of land to grow vegetables. “To plants seeds and watch them grow, to cultivate tranquillity, that is what is most important to me moving forward.”

Vivero Alamar (Photo: Jennifer Allsopp)

East of the city a few miles is the farm cooperative Vivero Alamar. A derelict piece of land, it was taken over by a group of four visionary people who cleaned it up and began growing food during the Special Period. Now it is a thriving farm, employing over 100 people. Base pay is between 350 and 700 pesos a month - a standard salary in Havana is 400 - with the potential to earn more based on productivity and seniority. Workers receive two meals a day, and work seven hours in the winter and six in the summer. Women with children are given the option of coming in an hour later. Everyone works five days a week and has a paid day off once a fortnight to deal with personal business. They have free, onsite manicure and barber services.

Cooperative business are the fastest growing sector of the Cuban economy, providing an attractive alternative or complement to state and privately-owned business.

Walking around with Eva, the daughter of one of the founding four, we see compost bins, rows and rows of emerald green lettuce, sunflowers planted to attract pollinators, corn to distract pests. Over a thousand people a week purchase their produce at the Vivero Alamar produce stand. “I had no intention of becoming a farmer. But now, I am proud to go everywhere in my rubber boots. I will be proud to have a career as an agronomist”, she says.

Eva has an interesting answer to the question of Cuba’s future. “It is no longer a fight between capitalism and socialism. We are in a transition to tierralismo.” Tierralismo translates as ‘landism’ or in a recent documentary of the same name, as ‘cultivating change.’ It strikes me as an important metaphor for the country as it searches for its way among the choppy seas of development. Change does not just happen; it is a process of cultivation and refinement. Certain seeds must be planted, tended, and nurtured if they are to survive into the future. As feminists, as activists, as those standing in solidarity with the Cuban people, our role is to listen and follow these leaders emerging from the Cuban soil.

This article was first published on 12 January 2015, and is republished here as the US and Cuba re-establish diplomatic relations and re-open embassies.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.