Laszlo Andor, former EU Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.Demotix/Pedro Benavente.All rights reserved.Over the last five years leaders in Brussels have focused their attention on the fiscal deficits of member countries that increased dramatically after 2008. It is no exaggeration to say that the central focus of policy and most EU summits has been supporting the euro through what austerity advocates euphemistically call "fiscal consolidation". Misdiagnosed and incorrectly measured, fiscal imbalances have simultaneously diverted attention from and highlighted far more important deficits in the European Union, of governance and social protection.

The manifestation of these twin deficits include 1) the continued stagnation of the euro zone economies; 2) the ongoing conflict between the Syriza government and the EU; 3) xenophobic fears of migrants; and 4) the appalling level of unemployment in several of the euro zone countries.

A few days ago yet again came news that the euro zone perhaps had finally begun a sustained recovery, though scepticism outweighed enthusiasm in most reports. What passed for recovery was an annualized growth rate of 1.4% for the first quarter of 2015 (quarter-on-quarter rate of 0.4%). Prior to the crash of 2008 a growth rate below 1.5 would have been identified for what it is, near stagnation, below what in a more enlightened time we called the "natural" rate of growth of an economy (productivity change plus the rate of population increase, usually estimated at 2.5-3% for advanced market economies).

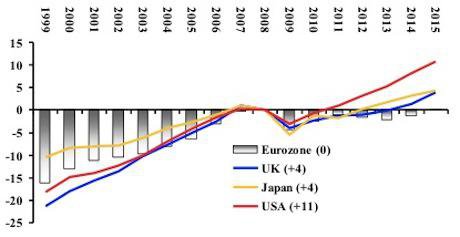

This unimpressive growth rate is not a recent failing of the euro zone, as the chart below shows, covering the years of the currency union (introduced as a unit of account in 1999). For comparison the chart includes the two largest advanced market economies, Japan and the United States, and the largest non-euro EU economy, the United Kingdom.

Prior to the crash of 2008 the countries of the euro zone grew substantially slower than both the United States and the United Kingdom, outpacing only notoriously stagnating Japan, a country weighted down in the 1990s and 2000s by a massive private debt overhang. Since the crash the comparison is even worse for the euro zone, stagnation more severe than that suffered by Japan before or after 2008.

If current projections, recently downgraded by the IMF, prove accurate, at the end of 2015 the euro zone will be at its 2008 level, while the UK and Japan will rise four percent higher, and the USA eleven percent higher. Except for those ideologically committed to fiscal austerity, the explanation of the modest-to-poor performance of the euro zone is obvious -- monetary union without a common fiscal policy, disastrously aggravated by a troglodyte vision that public budgets must "balance".

On the same day that much of the media reported a possible euro zone recovery, the head of the European Central Bank warned during a meeting with the director of the IMF that the economy of the currency union was too fragile for him to bring "quantitative easing" to an end. For her part, Christine Lagarde reminded Mr Draghi of the obvious, that little progress would come via monetary intervention without fiscal policy.

Euro zone, UK, Japan & USA, Level of GDP compared to 2008 (percentage point differences)

Projections for 2015. Numbers in legend refer to 2015 values. In order to include non-EU countries, the source is OECD, Economic Outlook

Far more serious in the immediate term than the deficit of policy instruments is the governance deficit evidenced in the conflict-filled negotiations between the Greek government and the finance ministers of the other euro zone countries. Whatever judgement one makes about the wisdom of either side in the argument, a few central facts cannot be contested.

First among these is that in January of this year the Greek electorate chose a new government, because it promised to reverse the policies of the previous government. The leaders of the EU both national and in Brussels refuse to accept this electoral mandate as binding, either on themselves or on the new Greek government.

To put the matter simply, the EU has no governance procedure to manage conflicts between national and supra-national rules and decisions, which casts doubt upon the role of the democratic process at the national level -- at least for the smaller countries of the euro zone.

This governance deficit is all the worse because of the ad hoc procedure for achieving the so-called bailout agreements between the EU and Greece (and also Ireland, Spain, Italy and Portugal among others). Once it became clear in late 2010 that such agreements would prove frequent, some specific legal guidelines should have been established. At the least agreements so fundamentally affecting national policy making called for greater participation of the European Parliament.

It is not relevant to argue that other governments in the euro zone have implemented austerity programmes, so the Greek government deserves no special consideration or concessions. In Greece for the first time the EU authorities demand a government complete a programme that it has neither designed nor has a democratic mandate to implement.

Xenophobia manifest in debate over immigration combines with high unemployment to demonstrate the other EU great deficit, the absence of a coordinated system of social protection. To my knowledge the only substantial EU-level program of social protection is the youth guarantee scheme championed by former Commissioner Laszlo Andor (see his SEJ article).

The absence of EU social support programmes reinforces perceptions at the national level that the main function of the "bureaucrats in Brussels" is to issue edicts that intrude upon "business efficiency" and "national sovereignty". These myth-ridden misperceptions are likely to overwhelm rational debate in the British referendum on EU membership promised by Prime Minister David Cameron. Media reports indicate that a majority of Conservative MPS may favour withdrawal. The front-runner for the Labour Party leadership, Andy Burnham, announced that he supports holding a referendum as soon as possible (though he favours continued membership). The stage is set for an acrimonious campaign in which far-right UKIP will thrive.

It is unlikely that a majority of voters in Britain or elsewhere will support EU membership because euro zone finance ministers zealously pursue reductions in national fiscal deficits -- on the contrary. However, a very large number of people in Britain and elsewhere may abstain or favour withdrawal because of the collateral political damage caused by the governance deficit and the social support deficit.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.